How the f— am I supposed to self-medicate?

+ the Phone-Walls Matrix, liminal spaces, and seriously guys should I go to grad school

I am about to talk more about staring at walls!

What started as kind of a joke I have now taken quite seriously for a few weeks, and it’s made me think a lot about self-medication, liminal spaces, and the values and purposes of both entertainment and boredom.

But first: A recap! When I say “staring at walls,” I mostly mean resisting the call (lol) of my phone, and, in the same vein, the call of TV and even of books and music at certain times. In the last blog, I explained how late last year this began out of necessity: my brain just felt overloaded with stuff (some trashy, some nutritious, but alas social value does not affect mental space occupied), and doing anything even mildly entertaining became deeply unappetizing.

Then, the less time I spent on my phone, the more sensitive I became to the unique qualities of phone time, mostly regarding its relationship to place and reality. That’s where the notes begin—from there, I consider why we want to numb out, how we enter and exit liminal spaces, how best to measure the methods of self-medication, and in the end, what tf I’m doing with my life, which is famously the most fun and un-stressful thing of all to consider!

Okay, chop chop. Here are the notes.

1. The phone is a metaphysical place

There are a lot of seafaring metaphors for the internet—”surfing the web,” for one, wanting to “throw your phone in the ocean,” for another, “being sucked into” TikTok or any social media, which I’ve always imagined as the kind of sucking a riptide or undertow does, “floods” of content, and so on. All of this implies that the the internet is like a vast sea, and to say one is “on their phone” implies the phone is a vehicle, like a boat or a surfboard, that allows us to traverse that sea.

But at this point, that’s not what the internet feels like, is it? Perhaps that’s how it once felt, when we went “on the computer” and dialed into the world wide web, but the internet does not function so remotely anymore. The lines between internet and so-called real life are blurred. Content online is not separate from you but has direct conversations with you, in real time. Even to describe someone as “being [extremely/chronically/etc] online” does not mean they’re literally doing business on the internet at that moment, but rather it means they dress, talk, move, act, and think in ways that indicate to you that they spend a lot of time online, generally on their phone, and it has affected the way they live their life.

The internet evolved and so did we. We are now amphibious creatures—we still go to work and eat and experience the world, but now we can also spend a very long time in the phonewater, and I’m starting to think you can’t really be in the phonewater and on dry land at the same time. Once you’re in there, you’re in there. Even if you think you’re good at multitasking, if one of those tasks involves phone, your handling of the dry land task is going to be significantly degraded.

So consider the seafaring language: “On your phone” doesn’t quite describe our modern enmeshment with the Life Internetic. I feel like it would actually be more accurate to say “in your phone” or even “under your phone,” as one might be “in the ocean” or “under the water.” This kind of change in language would more properly describe not only the quality of today’s internet but also the commitment one makes when spending more than 10 minutes online.

To say “I’m just on my phone” sounds casual. “I’m in my phone” sounds like a more mind-altering undertaking, which it is. The phone is a metaphysical place, and although it takes little effort to enter this place, be prepared to feel some weird and lasting effects while in it and after you leave.

Once I started thinking about phone time like this, I was much more able to reason myself out of going on my phone. Like, swimming is fun, but do I really want to get all wet right now? I’ll have to redo my hair…

2. There are some good things about the phone

Like Maps, but not for checking when the bus comes. Just wait like 10 minutes. It’ll come eventually. Patience is a virtue.

Or like the Sleep mode in the Health app, which reminds you when to start winding down at night and is good for sleep hygiene, which is easy to forget about. And the Sleep mode alarm is adorable.

Or like looking up recipes or, on occasion, places to go for dinner. That said, getting a restaurant recommendation or recipes from someone you know personally can be better in a sense, even if the food ends up worse.

Texting is good, up to a point.

Find My Friends is mostly unnecessary.

3. Being in the phone is like doing drugs

This is well-documented and nothing new! I am also not a scientist and know very little about how the brain works chemically. But I’ll offer this experience: The other day, after having not really scrolled on TikTok for about a week and a half, I scrolled for like an hour between getting home from work and going to a yoga class, and once I was in the yoga class I felt like shit. I felt weak and mentally scattered. All other variables (sleep, social interaction, meal times, etc.) were unchanged, so I really think the scrolling fucked me up physically. I got lost in the phonewater and it’d leached the strength out of my muscles. Creepy!

This made me think that I really need to treat phone time like doing drugs, and either set aside an entire day to wrestle with the effects (like tripping) or indulge for a brief period at the end of the day (like smoking weed). Or the occasional morning-time weekend indulgence.

4. That said, I see the benefits of numbing out

and phone time will surely do the job. And so will drugs, alcohol, long bouts of exercise, most forms of entertainment, and, sustained long enough, staring at walls.

By the second week of staring at walls I began to realize that all of this was about self-medication: Life is difficult and painful to endure, and we all need ways to release the pressure. I began to rethink the way I’d qualified phone time and wall time, which I’d conceived in opposition to one another: Phone = noisy, poisonous, bad; walls = quiet, nourishing, good. But if they all serve the same purpose in the end—to enter a different metaphysical space and leave your reality behind for a bit—maybe I’d been too harsh on phone time?

But that couldn’t be right: Done for the same amount of time, scrolling and staring at walls feel very different.

5. Liminal spaces: Entry and exit

I’ve heard before that people are addicted to their phones because they have a latent death wish: the possibility of “turning off” the brain for a limited time is very enticing. While staring at walls is often framed very differently—zazen (sitting meditation) offers the possibility of enlightenment—this also suggests the possibility of leaving the body behind and entering a new metaphysical space.

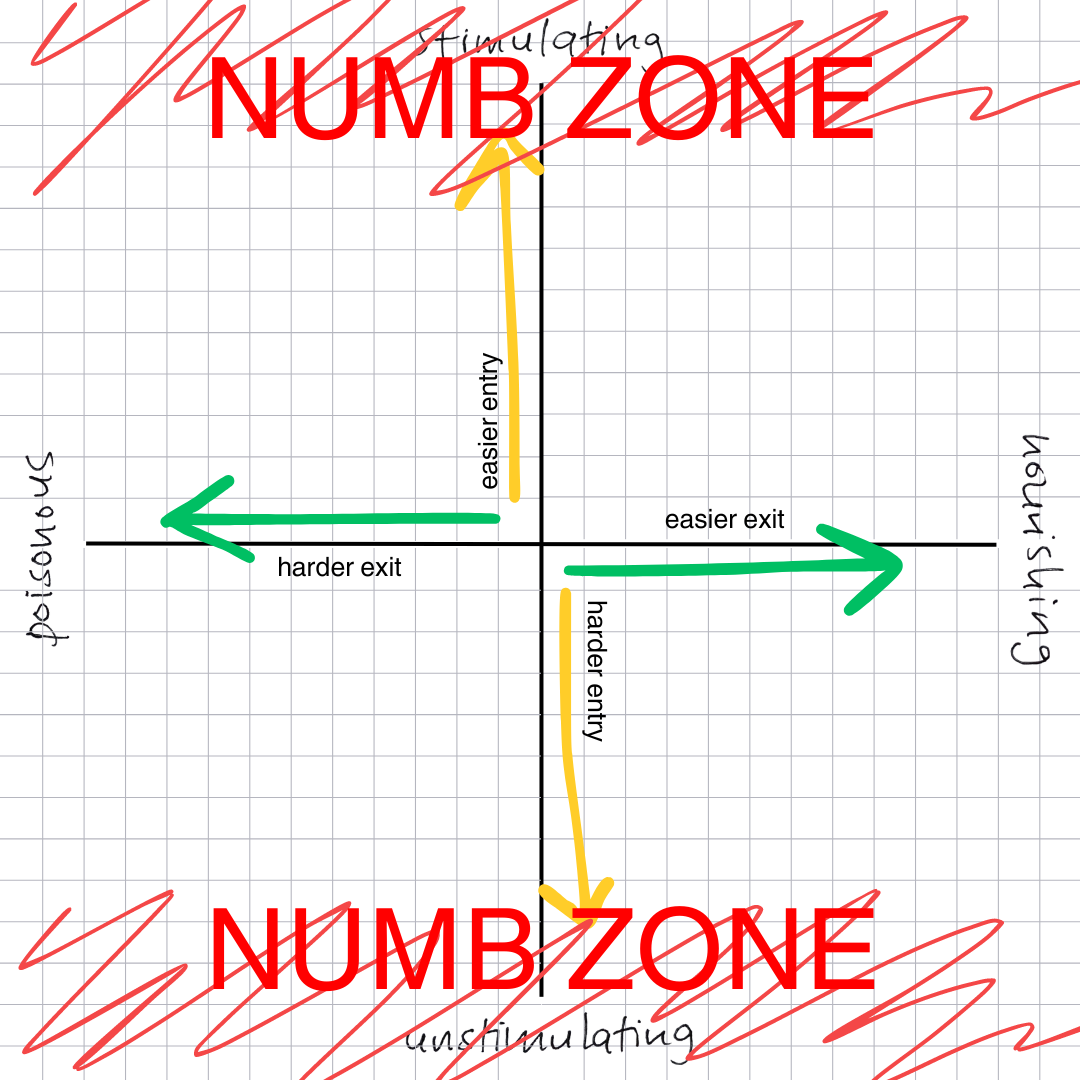

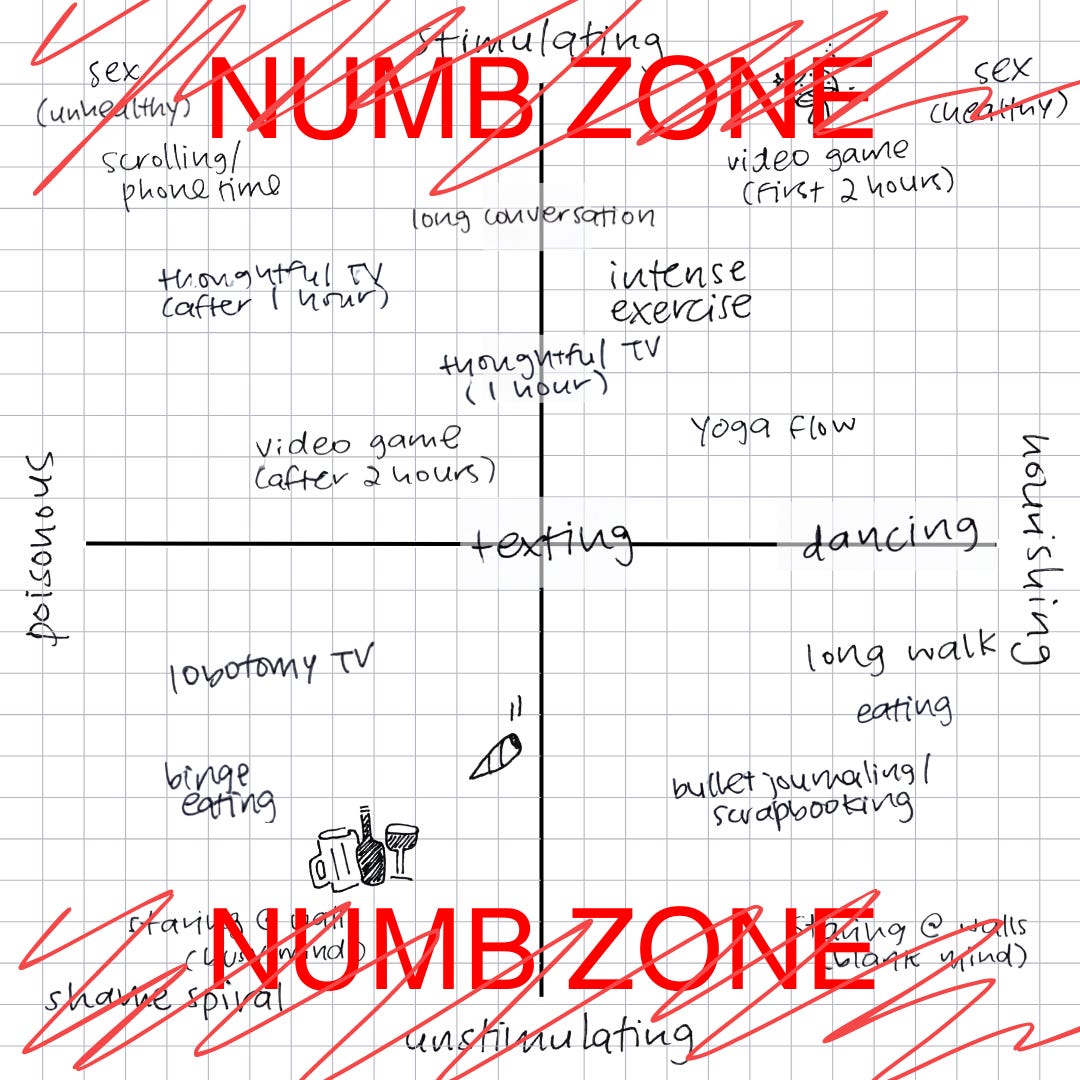

I began to think of the numb state as a liminal space, in between daily reality and death/enlightenment. This reframing began to answer some questions about why phone time and staring at walls feel so different: By definition, liminal spaces are only meant to be inhabited briefly, but different amounts of external stimulation changes the effort needed to 1) enter and 2) exit the liminal numb state. Numbing out can be nourishing, but if we stay too long, things start to get poisonous.

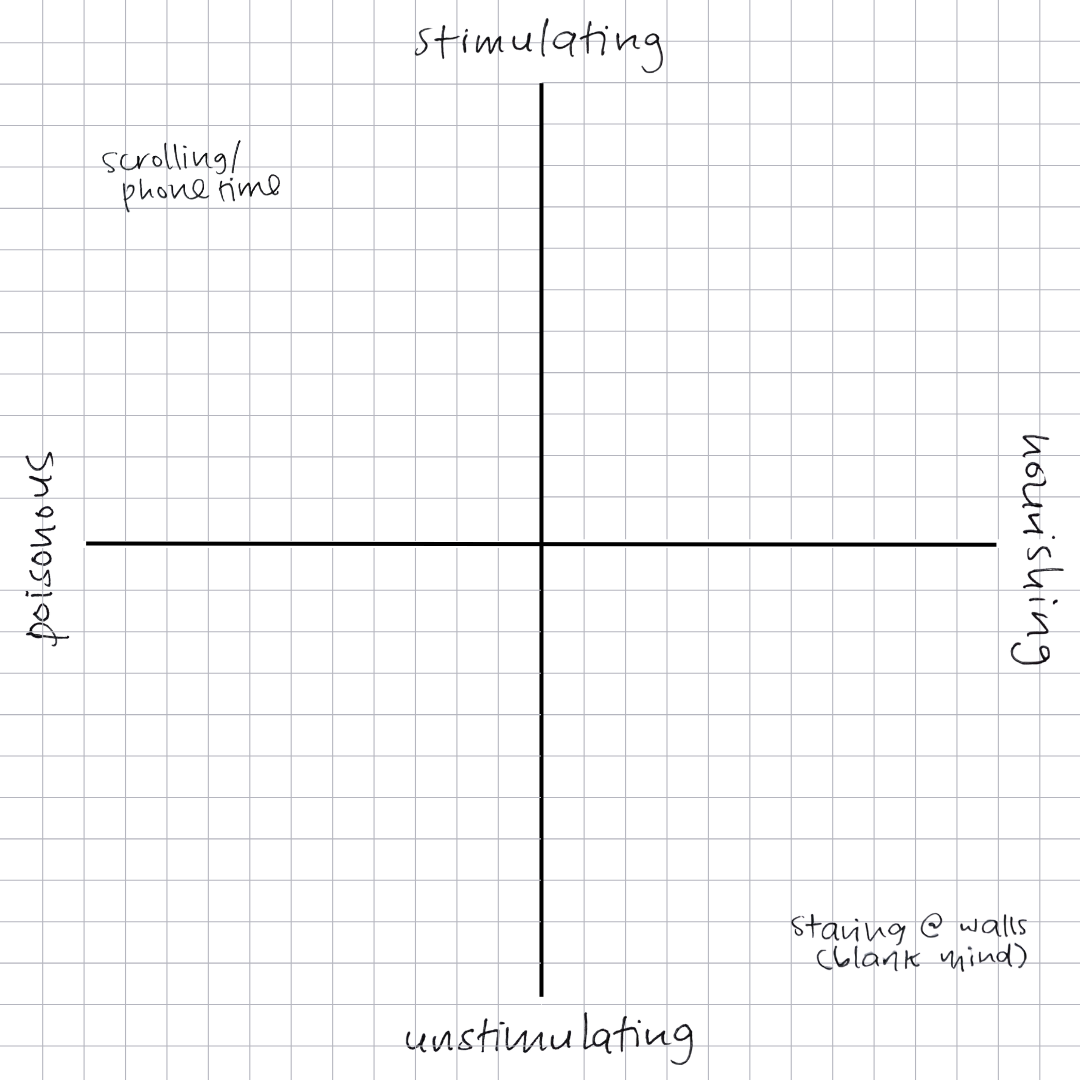

So, phone time, which is all external stimulation, is an easier entry but a more difficult exit—like I said, when you’re in there, you’re in there, especially if you enter with the explicit purpose of numbing out (scrolling). (Using your phone for something quick like texting makes both entry and exit unlikely.)

Staring at walls, daydreaming, meditation, etc., can also numb you out if you really do it properly with a blank mind. This route to numbing out is a more difficult entry, easier exit. It takes a mental effort to slip into a daydream: you have to let your mind lose momentum naturally, which is an uncomfortable process for the first several minutes. Once you’re in there, though, there is only one force (the mind, occupying itself) keeping you in that space, which can easily be overpowered by your body, like if someone taps you or you have an itch or have to get up and pee.

On the other hand, exiting a numb state entered via phone involves two forces (the mind, being occupied; phone, occupying), and the body is outnumbered.

There were too many variables to weigh mentally. I had to measure this visually. Like any respectable social scientist, I decided to make a 2x2 matrix.

6. The Phone-Walls Matrix

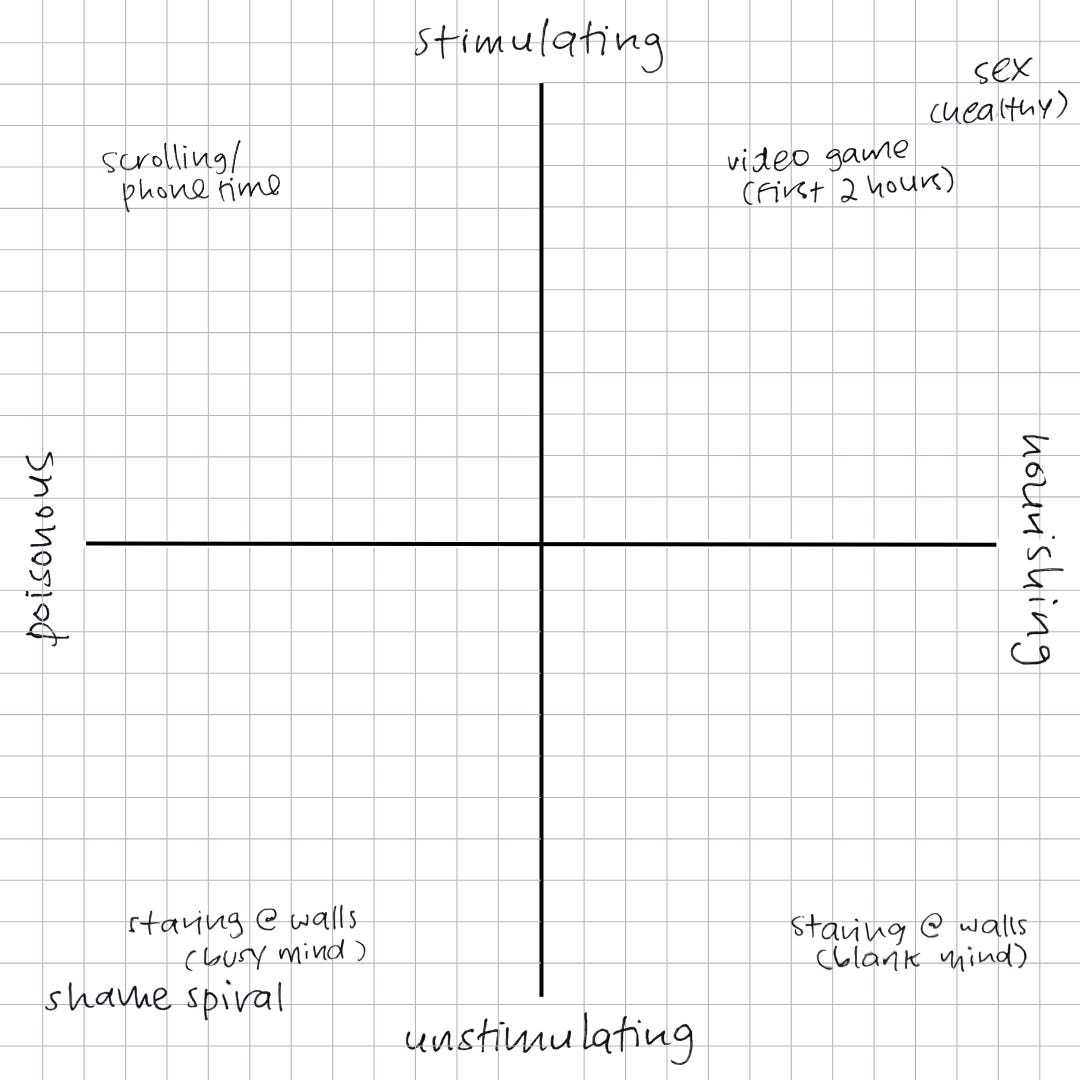

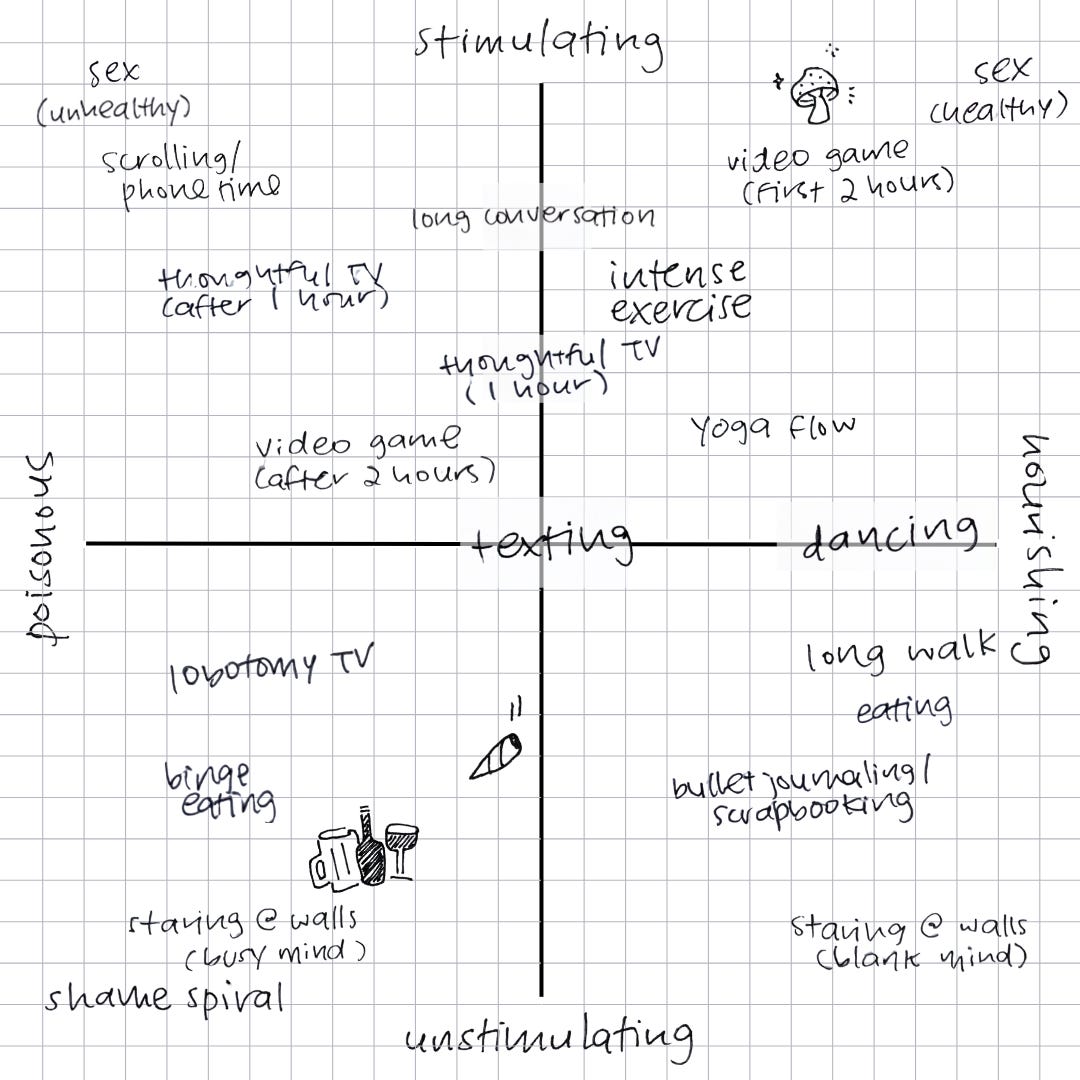

I set the matrix up to measure methods of self-medication on spectrums from stimulating to un-stimulating, and poisonous to nourishing.

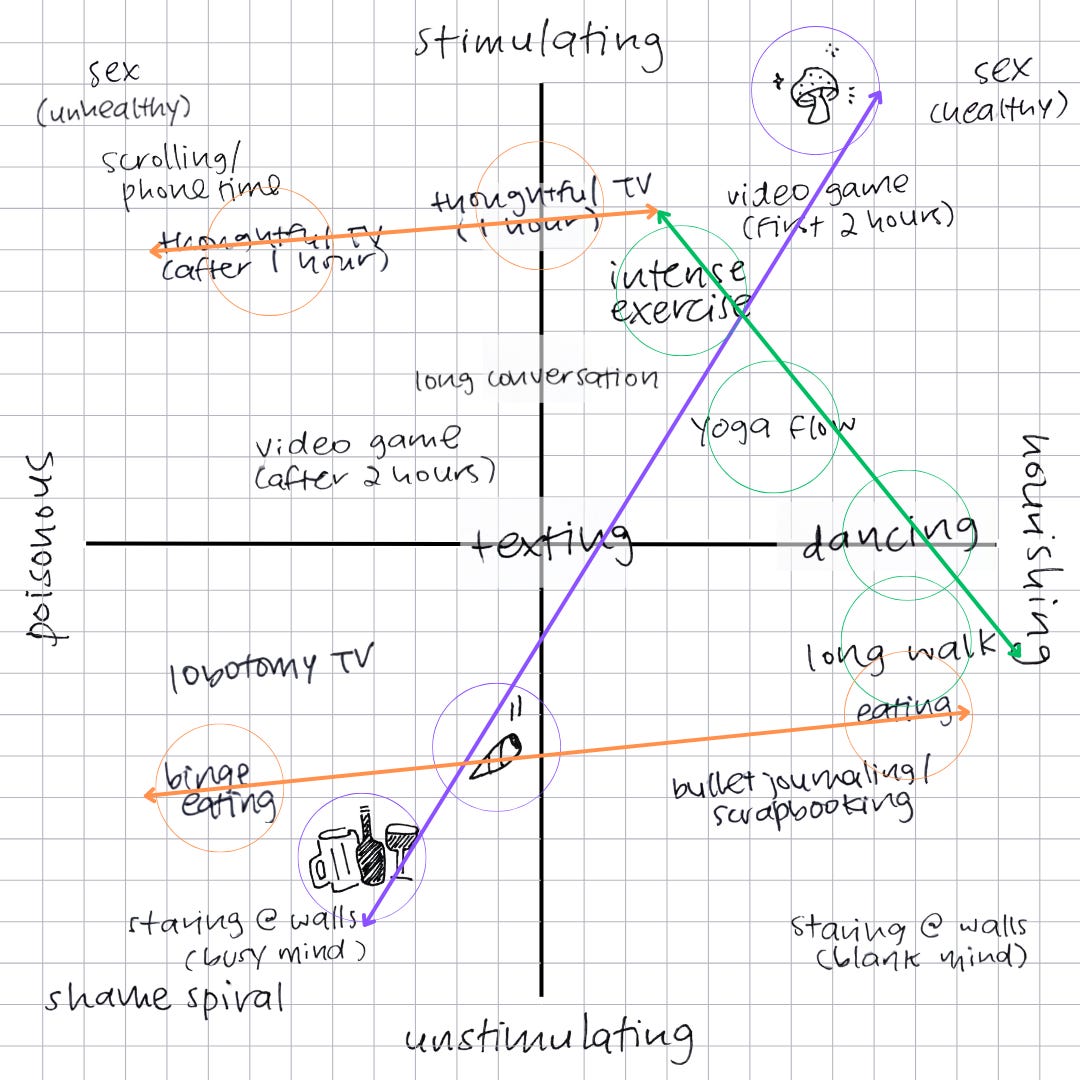

My ultimate theory is that the most and least stimulating ways of self-medicating, done for long enough, help us enter the liminal numb zones, which we clearly crave.

If we want an easy entry, we choose methods that plot further up the Y axis. But the further one moves along the X axis, the harder it is to exit, and there we run into trouble. (In many cases, this stickiness is what makes it poisonous in the first place.)

I charted my original reference points: Phone time and staring at walls.

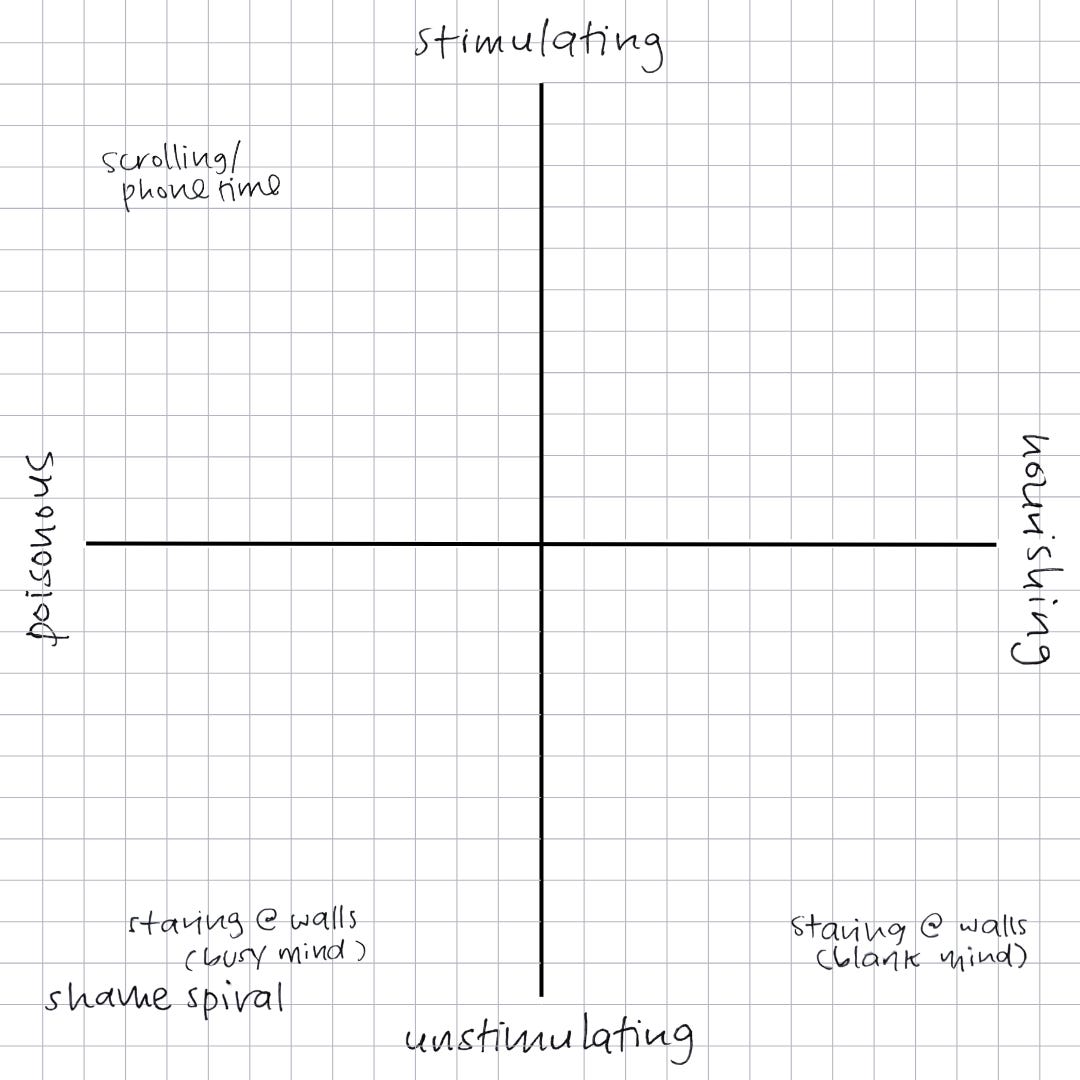

After doing it for a couple weeks, however, I know that staring at walls is not always accompanied by a blank mind. Staring at walls with a busy mind—and it’s more intense cousin, the shame spiral—charts differently.

Then, I filled in the last corner with the most stimulating and nourishing self-medication methods I could think of…

…and filled in the rest.

I noticed there were trends among groups of similar activities, like exercise (trend in green) and substances (trend in purple). Further, some initially beneficial activities simply become more poisonous and slightly less stimulating when done ad nauseam (trends in orange).

The matrix isn’t perfect. Done longer or more intensely or in different contexts, most points would move elsewhere on the Phone-Walls Matrix. Like, not every video game is so nourishing from the get-go. Not every time getting drunk is poisonous for the spirit. And what about when you combine methods, like texting while watching lobotomy TV? Or having a long conversation while on a long walk?

Unfortunately, plotting the numb zones on the filled-in matrix doesn’t totally make sense because of all the variables I mentioned above.

Ay. I wish I knew how to animate. Then we’d really be cooking with gas.

After all this thinking, my conclusion is that we are kind of just throwing shit at the wall and hoping it lands in the right spot to make us feel the right amount of better for the right amount of time before we need to come back to reality.

It’s a balance I guess.

7. And finally: Should I go to grad school?

Clearly, I find all this very interesting and have thought about it seriously.

So seriously, in fact, that I have also started to entertain the idea of quitting my job and applying to PhD programs so I can do some serious research and write a thesis on internet philosophy, because I feel like I’m on the precipice of some serious theoretical excavation. And before you tell me I should actually apply to seaside mental institutions for the manic depressive (do you think I’d get in?? hehe ◕‿◕✿) rather than PhD programs, I’ll tell you that I floated this idea to one of my most sensible friends and she said, and I quote, “For most people I’d say no definitely don’t do that, but you’re such an intellectual that I could actually totally see that for you.” So ha!

Obviously, I’m mostly kidding—we all know that once you start thinking grad school is a good idea, you can usually be sure that grad school is actually a terrible idea and you should just buckle up and ride the wave of whatever quarter life crisis is occurring at present.

But still…given some years of some g-d peace and quiet and a dedicated mentor to help me think things through, I do think my eventual thesis could really shred.

Thank you for your inspiring Substack! Your content consistently stimulates and nurtures my mind. Yet, I find myself grappling with the distinction between "Stimulating" and "Unstimulating." For me, activities like staring at walls, eating, taking long walks, and engaging in journaling or drawing are undoubtedly stimulating, but it seems to be tapping into a different, more profound realm of my mind. Perhaps it's akin to "Surface stimulation" versus "Deep internal stimulation."

This is so so good, the metaphor of being “in your phone” and “phonewater” perfectly describes the experience. Well-done, glad I discovered your blog!