The elite capture of Substack

This is Cydney Hayes, reporting live from the epicenter of the vibe shift

One thing I’ve learned as I’ve gotten older is that, no matter how much you try to change them, eventually you’ll find certain parts of yourself that just are the way they are. These parts of yourself are not always the way you want them to be, or the way other people want them to be, but it’s often in your best interest to let them be, and let them inform who you are naturally. I’ve written about this a bit before: Yes, yes, people are capable of change and personality is a myth, but the fact remains that you’ll find some aspects of yourself are fluid, and others are basically fixed. For example, when I was 12 I used to try to do all these workouts to make my legs slimmer, as, you know, 12-year-olds tend to do, because one time at recess a friend poked my thigh and said “Wow, huge.” And like, lol! Thanks girl! For a long time I thought the solution was to generally lose weight, but after living many years at many different weights I know now that I just have thick legs. That’s just what they look like, they always have and they always will.

Another one of these fixed qualities that I’ve found is that I am pretty uncompetitive, particularly when the boundaries of the competition are vague and the objective is intangible. In those cases, when no one knows what they’re doing or what exactly it is they’re supposed to be competing for, people usually manage all that obscurity by making as much noise as possible. I am not into this! I know this about myself. If the game involves trying to get more attention than the guy next to you, I want to bail immediately. These kinds of games include climbing corporate ladders, impressing at dinner parties, and succeeding as a creator on social media—and more and more these days, that includes Substack.

The vibes are shifting on Substack. Have you felt it too? What began as a creative underground sandbox (or at least, what began as something that felt that way) is becoming another greedy, feedy social media platform. (By feedy, I mean it’s a feed.)

What went wrong?

Here’s where I think it started: On April 5, in an obvious grab at Twitter’s user base about a week before Elon Musk officially bought the company, Substack rolled out Notes. The announcement post is really clever. In it, the three co-founders—Chris Best, Hamish McKenzie, and Jairaj Sethi—avoid explaining why Notes is a necessary addition to Substack; instead, they basically say that they made Notes to empower writers by democratizing the system: You’re able to engage with your audience more directly, you can more widely share your content, and best of all you could see your heroes, literary groundbreaker Margaret Atwood and fellow literary groundbreaker Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, going back and forth about a new piece by a smaller writer—which implies, that could be…you!

The article presents Notes, which looks and functions exactly like Twitter, as something totally new and totally in line with Substack’s original mission to create “a new economic model for culture.” But it feels slimy. Like any great work of product marketing, the Notes announcement post addresses everything you’d start to say before you can say it. (Like, “A subscription model isn’t new?” “How is this in the interest of smaller writers?” “Isn’t this just going to create content farms?” “Have you guys heard of Twitter???”)

Then, a few months later, on September 20, Substack announced they were making Notes the homepage. That post is a great example of culty “mission-driven” marketing language, too. It assures you that even though an endless scroll of Notes is now the homepage, you’ll still be greeted up top with your new reads, and that this emphasis on short-form content is all in service of helping you monetize your long-form work, the important work. Unfortunately—or intentionally! if we want to get conspiratorial with it!—the horizontal scroll of Read Next cards is ugly and actually doesn’t work that well: Sometimes it shows me posts I’ve already read and sometimes it doesn’t show new posts from the writers I subscribe to at all. So you learn to skip over it, and where do you go? To Notes to scroll forever.

The lack of ads is the one real thing that the founders have to say about what makes Notes different from Twitter. In both feature release posts, the Substack team reminds you that they built Substack to give writers an ad-free space to build an audience, connect with other writers, and make money free from the interests of publications or corporations. But it’s false advertising to position this as a failsafe that will ensure that Substack doesn’t end up like the social platforms that “make people dumber, pettier, angrier.” Every tech company starts out saying our product will change the world, and we’ve seen again and again how they turn artists into content creators and end up as screaming content farms where un-nuanced, easily digestible content dominates and corporate interests profit. I am also 100% sure advertisers on their way to Substack—if not in in-feed advertisements, then at least in #sponcon, and then eventually in brand accounts.

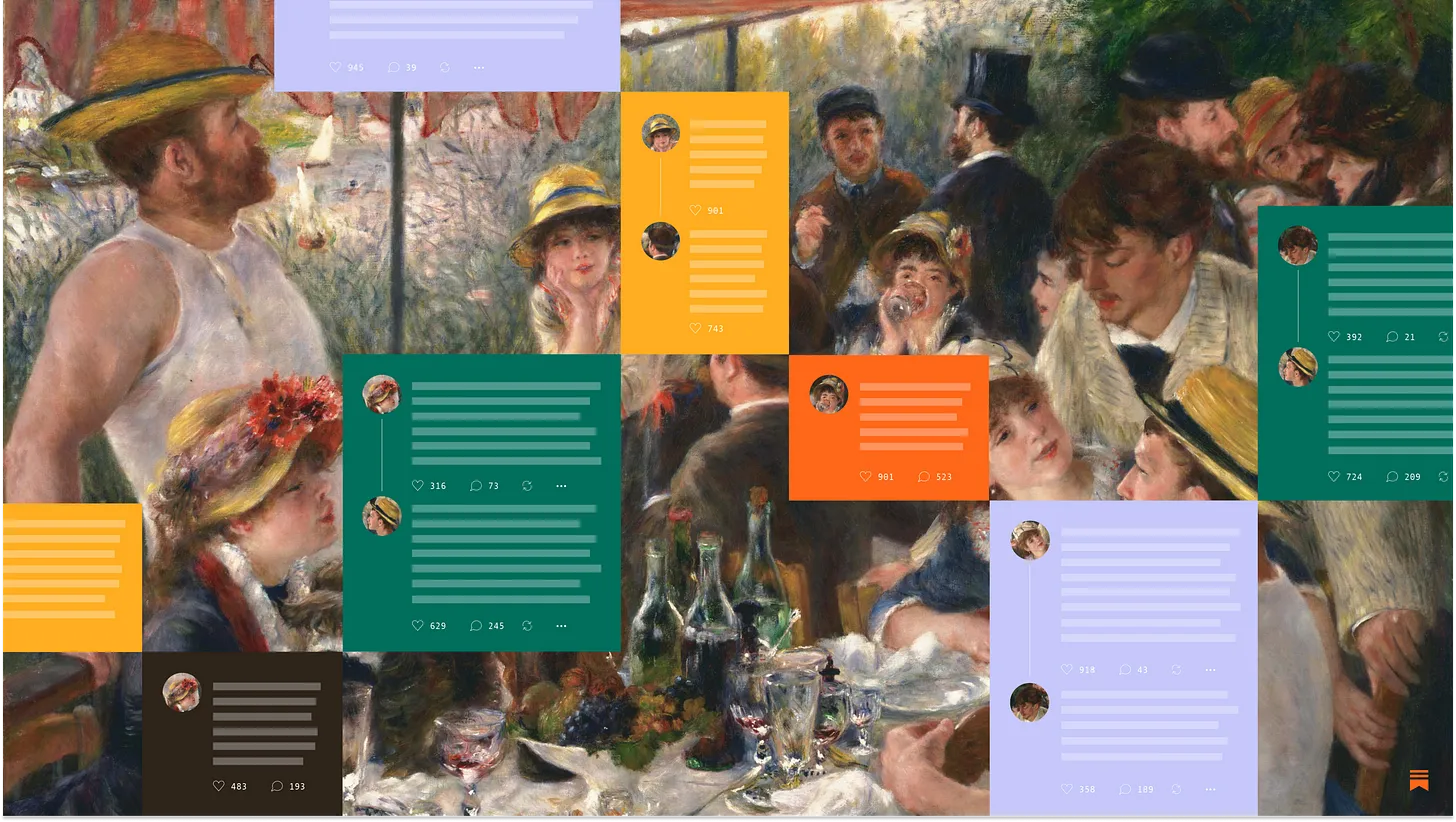

I also literally need you to see the cover image for that post—it’s a beautiful Renior painting from 1881 called Luncheon of the Boating Party, depicting a lively group of young people—a seamstress! an actress! a journalist! athletes and politicians!—crowded together, eating, drinking, discussing art and culture and 1881 politics. But what’s this, obstructing your view of such merry-making?! Oh, they’re all ON NOTES! Loool. It’s so on the nose. I’m laughing laughing laughing!!!

Unlike what marketers would have you believe (if you’ve ever worked in marketing, u get it! heh ಠ‿ಥ), the users on any given social media platform are not dumb. By now people are well-versed on social media algorithms. I think most people understand that the powers that be at Substack HQ want you to engage with their platform because it gives them user data and site traffic and other things they can show to investors to keep their business on the up and up, so they’ve built their product so that the more you engage on the platform, the more subscribers you get, so you’ll engage more, and the cycle continues. I also think that most people understand where they need to invest their time when, other than publishing a new post, the majority of the engagement actions now available on Substack are wrapped up in Notes.

And so the vibe has shifted, and here we all are, flopping around on Notes, diligently engaging, restacking and restacking restacks, commenting and sharing and slobbering over other writers’ stuff always a little bit in the hopes of getting noticed and getting subscribed to.

And this makes me want to bail! Which sucks because I know there are writers on here with really interesting ideas and worldviews, people who I could learn a lot from, and I know there are readers on here who might feel that way about me. But, like every social media effort I’ve ever undertaken, the vibe shift makes me wonder what we’re all doing on Substack anyway.

What is the goal? To get subscribers? If we have a lot of subscribers, does that mean people are reading? So is that the goal, to have people read our work? And then what? I mean that sincerely. Then what? To change hearts and minds? To start conversations? To make yourself known? Why to strangers? Why not to your family or friends or people in your actual life? Why are we all online, on Substack, circlejerking on Notes and posting on a cadence set not by our most compelling waves of inspiration but by our digital landlords, quality of our work be damned?

I would wager that the most common goal of a Substack writer is to accumulate enough paid subscribers that they can quit their day job and write for themselves full time. It says as much in the Notes announcement. For any writer on here, that would obviously be great, but that’s not how social media companies set things up to work, and despite the cool pep talks from its founders, Substack is no different.

The vibe shift we’re feeling is called elite capture.

What’s happening to Substack is a case of what philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò calls “elite capture.” By Táíwò’s description, elite capture is not just rich people being greedy: It’s the result of the systemic force that arises naturally within a group that has some kind elite/non-elite, stratified dynamic. (This is most groups within society.) To define it, he quotes economist Diya Dutta:

Elite capture is the “presence of unequal access to power…and consequently the ability to influence the transfer of funds/resources disproportionately” toward outcomes that benefit those with access.

Here, funds/resources mean currency, so in some situations they can refer to things like housing and healthcare but they can also refer to “knowledge, attention, and values” (Táíwò), values as in qualities that are considered good, legitimate, and important. So on Substack, it’s not so much that Hamish McKenzie & Co. are secretly boosting certain writers’ metrics behind the scenes to create a new elite, it’s more than they’re releasing new features, like Notes, that help change what we’re valuing and what we consider measures of success on Substack.

I think this is why I’m so uneasy about Notes and the direction that Substack is headed. When I first started writing on here, I felt like the values were ideas, quality writing, and honesty, but now writers seem to be rewarded for algo hacks like posting on a schedule, commenting, liking, restacking. The distortion of purpose, which may have originally been to “meaningfully contribute to discussion or take pride in the quality of one’s work” (Táíwò), is classic elite capture: Game-like interactions eventually reward the user with vanity metrics like views, likes and comments on their posts, subscribers (and followers, perhaps the dumbest feature on Substack, as it only serves to further abstract performance metrics from any actual writing), and eventually one of several checkmark badges that essentially denote who is part of the elite (and how they rank within it), and who is not.

So to be less internet-y about it, the shift in vibes is really a shift in values: From quality to quantity; from recognized intellect to symbolic trophies; from growth in our collective writing skills to growth in subscribers, and in turn, growth in users and profit for Substack.

Can symbolic rewards turn into real ones?

In my very first post on Substack, I said that I felt like a prospector come to California in 1850. For my non-Californians, this is two years after gold was discovered near Sutter’s Mill. Metaphorically, it took two years for word of the Gold Rush to travel to me and for me to go and claim my spot near the river—and by then what was once an empty hillside full of gold was now a competitive marketplace. I can still set up my station, but in the end, the people who pan for gold aren’t the ones who are going to strike it rich—it’s the people who own the land you pan on. (For giggles, guess where Substack is based. Lol. Gold Rush over and over.)

It turns out, this was an appropriate metaphor. In September 2021, about two years before I got on Substack,

—who is arguably the most well-known writer on Substack specifically for writing on Substack—sent out her first newsletter. It took two years of sometimes seeing her on TikTok and thinking to myself, she seems smart and has interesting takes, I want to read her long-form stuff, for me to start thinking I could do what she did. Then, soon after I started writing on here, she posted that she’d sold a book. And for a writer on this platform, that’s the dream! To turn writing in obscurity into a self-sustaining and celebrated career by posting blogs uncorrupted by the profiteering whims of publications and building a following on Substack. What I was missing at the time was that 1) I think (?) she already had a lot of followers on TikTok and maybe elsewhere, and whatever fraction followed her over to Substack was still a big number, and 2) RFQ is primarily a writer but also a very hard-working content creator. She grew her audience not just by writing but by marketing her writing and, perhaps in larger part, herself. That, I’m not sure I’m built to do.Gone the way of Ashley aka Bestdressed on YouTube, RFQ doesn’t post on Substack nearly as much as she used to. When the It Girls leave the platform they once dominated because they have more prestigious and lucrative opportunities to attend to offline, you can safely assume that you are not an early adopter, and that your odds of striking gold are much, much slimmer than they were when the soon-to-be-It Girls were first setting up their tents near Sutter’s Mill.

Don’t get me wrong, I’ll keep writing on here. For the most part, I like the writer UX (although I do wish there was more visual customization) and I have around 100 subscribers. Which is not a lot when compared to the people who go hard on Notes and succeed in getting attention, but by a different measure it’s still 100 people who care to hear from me, and it’s enough people that I could not fit them all in my apartment, and it’s a lot. Could I make moves to get more? Sure, but with Substack becoming what it is, the problem is that even if you jump through all the social media marketing hoops Substack releases over the coming months/years, there’s no guarantee of success and the psychological cost can be high.

One of the big losses I see in the vibe shift is the opportunity for writers to loose themselves from the chains of personality and just write interesting things. A succinct elevator pitch for your newsletter is much more marketable than being a whole person who communicates their ideas via blog. That said, some people, including me, market their blog as a publication dealing in existentialism and philosophy and the chronicles of life in the world today, which leaves room for your perspective to change as the world does. But to convince someone to consistently hear your thoughts and hang in there while you figure out your shit, you first need to convince them that you are worth sticking around for, and that requires marketing yourself, which means choosing which parts to label, package, and sell, and which to chop off and hide in the back room.

Before I go on I will say that, aside from marketing ourselves, perhaps the biggest loss in the vibe shift is simply the time we now spend scrolling Notes instead of reading people’s writing. There’s not much more to say about that: That’s just what happens when the platform is built as a feed, and it’s an L.

Anyway—I want to say that maybe it’s just me who finds marketing themselves, especially within the machinery of a big tech corporation, to be gross and deadening, but I know that’s not true. Recently I’ve seen so many other people say this, or some rumination on this (it came up in a recent piece from Briana Soler, this one from Mary Wallace, on Embedded, on Humans of New York, and it’s Lee Tilghman’s whole thing). I’m sure after I post this I’ll find 10 more. What effect internet performance and self-branding has on our psyches, not to mention our society and our economy, may be one of the most essential questions of our time.

So what happens from here? If half of us are screaming over each other on Notes and the other half are unsatisfied with all the screaming, it’s likely new elites will emerge from the screaming half, and the unsatisfied half will fade into obscurity. Or, in a less likelier case, maybe the vibe will shift in reverse. But as the founders said in the Notes announcement, the point is not to go backwards. The point is to build something new.

If Substack’s a bust, where do we go?

I can’t give the founders too much credit because it’s turning out that they did not build something new (they just built Writer Twitter, which already existed on Twitter), but I agree with the sentiment. It’s also how Táíwò bookends Elite Capture. Building something new would be “a worldmaking project, aimed at building and rebuilding actual structures of social connection and movement, rather than the mere critique of ones we already have.” In other words, we can’t just rearrange the furniture inside rooms we don’t like the shape of; we have to build entirely new rooms in better shapes.

We won’t be able to achieve the things we want on platforms run by dudes interested in VC money and endless growth. Or at least I won’t be able to. I guess it depends on what you want. If you want attention, you could get that. If you want money, you could even get that. But at this stage in the elite capture process Substack may never provide with you enough money to quit your day job, or enough attention to parlay subscribers into a book deal like Rayne Fisher-Quann. That said, the hope of achieving your goals is always higher if you know what they are, so ask yourself: What am I doing here?

Here’s mine: After some thinking, what I want is to 1) write because it’s fun, 2) practice creative stamina and self-discipline, 3) chronicle what I think about the world for my own posterity, and 4) offer up the idea that there is a different way to live.

I hate to bounce after opining on problems without suggesting solutions, so here’s my POV: You can still write online, you can even go crazy on Notes, but if you really want to penetrate the social reality, be sure to leave yourself enough time and energy to do things in person. Making moves offline is one of the most pure and radical things you can do now. And it’s comparatively much more effective (see: protests—you can’t shut down the means of production or obstruct transportation infrastructure by posting on your story, even if the content is rich and true). If you want to be a cultural critic who actually influences culture, to worldmake, make a name for yourself in the place you pay taxes. Make friends with your neighbors, tell them you’re a writer, share your blog with the ones who like reading things. Do or host open mic readings, where you can talk to people about art and culture, say your piece on the current state of things, and hear what other people think about the world. Observe what’s happening in the world that is actually around you, write it down, and distribute it to people in physical form. Make experiences offline, and ask people to their face, “What are we all doing here?” It is a lot more difficult for the elite to capture you when you are not a set of user data but a real breathing, sweating, thinking person, taking up space in a room with your thick legs.

Thanks for writing a thoughtful critique (even if it does come with some stingers!).

I found and read this post because a writer I admired liked it and it showed up in my Notes feed.

Notes is not meant to be a data grab. That’s not our business. Our business is helping writers make money—because that’s how we as a company make money and then get to build all the things that hopefully result in a better media ecosystem.

Notes is intended to be a better discovery system for great writers and writing, and to drive subscriptions to writers. In the absence of Notes, writers instead tend to get found via other platforms like Instagram and Twitter, which really are data-grab plays and are based on rules that care a lot about maximizing revenue and very little about healthy discourse or the quality of a writer’s life. We want that system to change and to be tilted in favor of writers. That’s what Substack is all about.

We’re in the very early days with Notes and the app in general. We’re always looking to improve and serve writers better. Critiques like this help and show us what to aspire to.

I came to Substack over 3 years ago and this is all spot on. My writing has stayed pretty much the same. I have a few thousand subscribers, not many of them paid. And I've made a commitment to resist doing what Substack says I should do, which is to market myself ALL THE TIME. No. That's not what I want.

I've also found that there are a few Substacks who position themselves as having the key to success and using that to gain paid subscribers. They give me MLM vibes. Substack loves them and lifts them up bc things like that increase their bottom line.

I've also noticed that pretty much no one on here grew their community on Substack alone. May folks with the orange check marks already had wide readerships or followings on other platforms, or are well known writers or public figures. Many of them received grants from Substack or were paid to start their Substack. No shade at all- many of these folks are incredible and I love them and their writing. But after having been here for so long I stopped believing that I can support myself as a writer here, and I also don't want to, because once you have a massive amount of paying subscribers you are beholden to them in ways that can (but don't always) detract from your own creative work, especially if you're doing work that requires long-term focus and development.

I love my little community of readers, but I know that they love me for me. Just for what I do. I don't write FOR them. I tried to do this for a little bit and the funny thing is that my work wasn't as good or authentic. In this way I think that Substack can be a lovely place of connection. We don't necessarily have to buy in to what the platform is selling, but not doing so may also mean accepting that our growth here is limited. I have a book coming out in a couple years so I do know that things could change, but that has nothing to do with Substack really! I think it's dishonest for anyone, including Substack, to purport that every single person can make a living here. It's just not true. And any Substackers who also perpetuate that myth are filling their pockets with people's mostly unfulfilled hopes and dreams, which imo is unethical, but whatevs, I guess they've got it figured out bc they're making way more money than me!